General Information about Ranitidine

While most people can safely take Ranitidine, there are some who should avoid it. This contains people who have a historical past of allergies to any of the components within the medication, those with kidney or liver illness, and pregnant or breastfeeding ladies. It is important to seek the assistance of along with your physician if you fall into any of those classes before beginning Ranitidine treatment.

In conclusion, Ranitidine is a generally used medication for the therapy of conditions that trigger excessive stomach acid production. It can provide reduction from signs corresponding to heartburn, stomach pain, and ulcers. Like any medicine, it is essential to follow proper dosage directions and inform your physician of some other medications you are taking. By doing so, you'll find a way to effectively manage your situation and improve your general health and well-being.

Stomach ulcers, also recognized as peptic ulcers, are open sores that develop on the lining of the stomach and may trigger signs similar to bloating, belly ache, and nausea. Ranitidine might help heal these ulcers by reducing the quantity of acid in the abdomen, permitting the lining to heal and preventing further injury.

Like any medication, Ranitidine may cause unwanted effects in some individuals. These could embrace headache, dizziness, diarrhea, constipation, and rash. It is important to seek the guidance of together with your doctor should you expertise any of those unwanted side effects or some other uncommon signs.

Ranitidine is available in both prescription and over-the-counter varieties. Prescription energy Ranitidine is normally taken once or twice a day, and over-the-counter forms are taken as wanted for aid of symptoms. It is really helpful to comply with the instructions of your healthcare supplier or the medication label when taking Ranitidine to ensure the correct dosage and duration of therapy.

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome is a uncommon dysfunction by which tumors in the pancreas or small intestine trigger the body to produce giant amounts of stomach acid, leading to stomach ulcers and other digestive points. In these circumstances, Ranitidine is used to control the excess acid production and supply relief from symptoms corresponding to heartburn, abdomen ache, and diarrhea.

Additionally, Ranitidine may interact with other medicines similar to anticoagulants, anti-seizure medication, and sure antibiotics. Therefore, it is important to inform your physician of any other drugs you're taking before starting Ranitidine therapy.

Ranitidine is a drugs commonly used for the therapy of situations that cause the physique to provide excessive quantities of abdomen acid. This treatment is used to relieve signs related to situations corresponding to Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, gastroesophageal reflux illness (GERD), and abdomen ulcers. It belongs to a category of medicine often recognized as H2 blockers, which work by lowering the quantity of acid produced by the stomach.

In patients with GERD, a continual condition the place stomach acid regularly flows back into the esophagus, Ranitidine might help alleviate symptoms such as heartburn, chest ache, and problem swallowing. It works by lowering the amount of acid in the abdomen, which in turn reduces the irritation and harm to the esophagus caused by the stomach acid.

This patient was found to have renal cell carcinoma that directly invaded this segment of adjacent small bowel gastritis hiatal hernia diet cheap ranitidine 300 mg with amex. Management/Clinical Issues If metastases to the small bowel are suspected in the absence of a known primary, a thorough search should be pursued for the primary tumor in the solid organs, thorax, pelvis, colon, and-for melanoma-skin. Key Points Metastases to the small bowel are more common than primary small bowel malignancies. Hematogenous dissemination, intraperitoneal seeding, and direct invasion are routes of spread to the small bowel. Mortele Definition the appendix, also known as the vermiform appendix because of its worm-like shape, is a blind-ending hollow tube arising from the cecum. Anatomy and Physiology the appendix, adjacent cecum, and ileum arise from the midgut. The open end of the appendix is called its base or root and its blind-ending portion is termed the tip; its body extends from the tip to the open end. At birth, the appendix arises from the apex of the cecum and is attached to the cecal wall at the convergence of the three taeniae coli. In childhood, there is asymmetric enlargement of the cecum with lateral expansion of the lateral and anterior walls, resulting in the relative migration of the appendix to the posteromedial wall of the cecum. By adulthood, the base of the appendix is relatively fixed and is located within 4 cm below the ileocecal valve. The position of the body of the appendix is highly variable; in over 50% it is retrocecal or retrocolic in location, with pelvic, subcecal, preileal, and right pericolic locations also described. The appendix usually ranges from 6 to 10 cm in length; however, extremes of length have been described. The wall of the appendix, like the remainder of the gut, is made up of four layers: mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and serosa. It is lined internally by mucus-producing columnar epithelium similar to that of the colon. There are extensive lymphoid aggregates within the mucosa and submucosa of the appendix. This lymphoid tissue is most prominent in children and young adults, gradually becoming atrophic with increasing age. Enlargement of this lymphoid tissue can lead to obstruction of the appendiceal lumen. The outer longitudinal layer is formed by the merging of the three taeniae coli of the cecum, a feature that can assist in locating the appendix at surgery. The mesoappendix is a double layer of peritoneum connecting the appendix with the small bowel mesentery. Radiograph of the pelvis shows multiple lead shotgun pellets within the lumen of the appendix in a patient with a long history of shooting game and not removing the pellets from his meat prior to eating it. The appendicular artery arises from branches of the superior mesenteric artery via the ileocolic artery. It is a terminal artery, which can predispose the wall of a distended appendix to ischemia. The appendicular vein or veins drain via the ileocolic vein to the superior mesenteric vein. Lymphatic drainage is through the ileocolic, superior mesenteric, and celiac nodes to the cisterna chyli. The appendix was previously thought of as an embryological remnant with little or no function. More recently, it has been suggested that the appendix helps in the modulation of immune reactions within the gut in the first few decades of life. Another postulated function is that it provides a reservoir of normal gut flora to repopulate the bowel after loss of the normal flora due to illness. Imaging the normal appendix is usually not identified on plain radiographs of the abdomen. However, radiopaque contents within the appendiceal lumen may indicate its location. Appendicoliths are the most commonly encountered radiopaque structures within the appendiceal lumen. These are formed from condensed pieces of fecal matter that calcify over time, rendering them radiopaque. The lumen of the normal appendix should fill with contrast medium at barium enema and during fluoroscopic studies of the small bowel, such as small bowel follow-through examinations. While nonfilling can indicate an obstructed lumen, it can be seen in normal patients and does not necessarily indicate pathology. Rarely, the appendix can intussuscept into the cecum and appear as an intraluminal filling defect. At ultrasound, the normal appendix can be visualized as a blind-ending tubular structure arising from the cecum in the right lower quadrant. Graded compression can be used to aid identification and involves the application of firm but gentle pressure on the right lower quadrant. This technique displaces the overlying bowel gas and shortens the distance between the appendix and the transducer. However, patient body habitus permitting, a high-frequency linear probe will allow better resolution.

The pathophysiologic insult leading to nodular regenerative hyperplasia in these patients is believed to be arteriovenous or portovenous shunting gastritis bad eating habits ranitidine 150 mg buy with amex, causing ischemia and atrophy of affected acini. Adjacent acini with an intact blood supply undergo compensatory regeneration and hyperplasia. These regenerative hyperplastic nodules compress the sinusoids and induce portal hypertension. In addition, focal nodular hyperplasias have been described in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia and presumably arise as hyperplastic responses to long-standing disturbances of blood flow. The peribiliary plexus arising from the hepatic artery provides the blood supply to the biliary tree. Shunting of blood from the hepatic artery to the hepatic and/or portal veins causes hypoperfusion of the peribiliary plexus and ischemic necrosis of bile ducts (extrahepatic, intrahepatic, or both), with the subsequent development of biliary cysts, biliary strictures, and secondary sclerosing cholangitis. Compression of the bile ducts by enlarged hepatic artery branches may contribute to biliary manifestations. Portosystemic encephalopathy may be present in these patients and can be explained by the shunting of blood from the portal vein to the hepatic vein and systemic circulation. Uncommonly, abdominal angina due to mesenteric steal into the hepatic artery (mesenteric "steal" syndrome) has been reported. Functional hepatic parenchyma is generally well preserved, but some patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia develop fibrosis and may even progress to cirrhosis. Contrast-enhanced maximum-intensityprojection reformatted image shows a markedly dilated common hepatic artery (arrow). Imaging Features Ultrasound can detect arteriovenous malformations and aneurysms associated with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia but not telangiectasias. Arteriovenous malformations are associated with enlarged, tortuous proper hepatic and intrahepatic arteries and large draining veins. Duplex Doppler reveals high-amplitude flow in the feeding artery, a phasic arterialized waveform in the draining vein, and turbulent high-velocity flow at the junction of the artery and vein. Hepatic arteriovenous malformations appear as arterialized pseudolesions associated with early-draining veins. Early drainage into hepatic veins indicates arteriovenous shunting, while early drainage into portal veins indicates arterioportal shunting. Arterioportal shunts typically are associated with transient hepatic enhancement differences. Because of flow effects, the large vessels associated with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia are usually hypointense on unenhanced spin-echo and fast spin-echo sequences and hyperintense on unenhanced gradient-echo images. Catheter angiography is the gold standard for the detection and delineation of arteriovenous malformations of the liver and subtle abnormalities such as portovenous shunts, and it provides a vascular map before surgical or angiographic interventions. An image through the liver dome reveals mildly enlarged tortuous hepatic arteries in the liver periphery. Early antegrade filling of hepatic veins (arrow) indicates extensive arteriovenous shunting. Ar terial Disorders 341 Mimics and Pitfalls the presence of nodular regenerative hyperplasia results in abnormal liver morphology, including a nodular liver contour. However, nodular regenerative hyperplasia is not true cirrhosis; histologically, the normal hepatic microarchitecture is preserved. Hypervascular lesions such as confluent pseudomasses are common in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Because the liver may have a cirrhotic appearance (as noted previously), these lesions may be misdiagnosed as hepatocellular carcinoma. Clues to the correct diagnosis include lack of visibility on unenhanced images and homogeneous arterial contrast enhancement with fading to isointensity/isoattenuation relative to the liver on more delayed phases. This 20-mm maximum-intensity projection of coronal reformatted images acquired in the arterial phase reveals an extensive and complex network of intercommunicating enlarged, tortuous hepatic arteries, portal veins, and hepatic veins. These combine to give the liver a diffusely and vaguely nodular enhancement pattern. Differential Diagnosis Multifocal arteriovenous and arterioportal shunting due to cirrhosis or hepatic tumors. Focal arteriovenous or arterioportal shunting due to postbiopsy or traumatic arterioportal or arteriovenous fistula. Multifocal hypervascular masses: Hepatocellular adenomas, focal nodular hyperplasia, hepatocellular carcinoma, hypervascular metastases. Management/Clinical Issues the diagnosis of hepatic involvement by hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia can be made by imaging alone; biopsy does not contribute to the diagnosis and should be avoided. In patients with asymptomatic liver involvement by hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, no treatment for liver lesions is recommended. In patients with symptomatic liver involvement, the goals of liver-directed treatment are palliation of symptoms and prevention of complications. Selective embolization/ligation and ablative techniques can be used to reduce the severity of intrahepatic shunting. Liver transplantation may be considered if the condition has progressed to the end stage. Imaging follow-up of both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients is necessary because disease progression may be silent. Once the diagnosis is established, genetic screening should be considered for asymptomatic family members. Classic triad: Epistaxis, multiple mucocutaneous telangiectasias, and positive family history. Hallmark imaging findings of hepatic hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: Intrahepatic telangiectasias and arteriovenous malformations; enlarged hepatic arteries. Major complications of hepatic involvement: Highoutput congestive heart failure, portal hypertension, nodular regenerative hyperplasia, biliary ischemia, mesenteric "steal" syndrome, hepatic encephalopathy, and, rarely, liver failure.

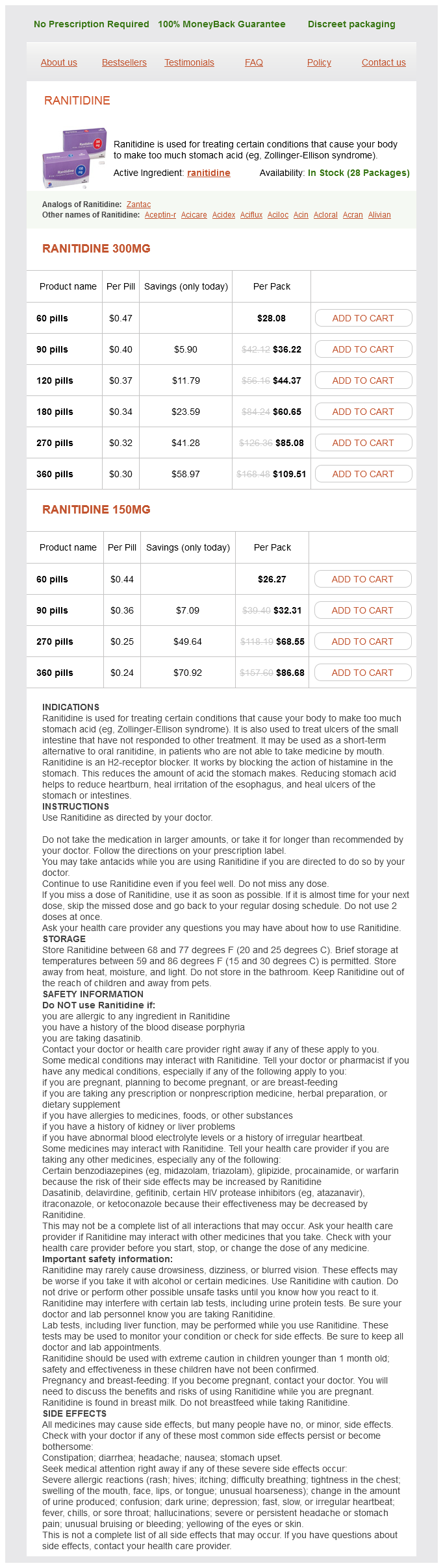

Ranitidine Dosage and Price

Ranitidine 300mg

- 60 pills - $28.08

- 90 pills - $36.22

- 120 pills - $44.37

- 180 pills - $60.65

- 270 pills - $85.08

- 360 pills - $109.51

Ranitidine 150mg

- 60 pills - $26.27

- 90 pills - $32.31

- 270 pills - $68.55

- 360 pills - $86.68

Early enhancement of hepatic veins during the arterial phase is also observed gastritis yogurt purchase discount ranitidine on line, consistent with arteriovenous shunting. Liver involvement in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia). Pathologically, liver infarction is characterized by anoxic coagulative necrosis of liver cells followed by infiltration of inflammatory cells, resorption of tissue, and scar formation. In patients with cirrhosis, regenerative nodules vulnerable to hypoxia may infarct after episodes of hypotension. Histologic evaluation depends on the acuity of the infarction and may reveal necrotic hepatocytes associated with zones of hemorrhage, congestion, inflammatory change, immature granulation tissue, or fibrosis. They are typically peripherally located and wedge-shaped, although location and morphology may vary. Acute infarcts are often ill defined; they usually do not enhance after injection of contrast agents or they may enhance heterogeneously with perfusion defects. Over time, infarcts become smaller, their margins become progressively more distinct, and they heal with scar formation. Postinfarct scars are revascularized and enhance progressively in the dynamic vascular phases after the injection of contrast agent. Enhancement is variable after contrast administration and depends on the underlying pathological changes. Zones of necrosis and hemorrhage do not enhance; zones of fibrosis show progressive enhancement; and viable zones may enhance normally. Abscesses or necrotic tumors: Rim enhancement, space-occupying lesions with mass effect on vessels and other structures. Liver Infarct Definition Liver infarct is defined as an area of ischemic necrosis resulting from reduced intrahepatic blood supply, most commonly after interruption of hepatic arterial supply in combination with one or more predisposing conditions. Demographic and Clinical Features Liver infarction is uncommon, since the liver has a dual blood supply as well as a rich arterial collateral network. Patients may be asymptomatic, have nonspecific complaints, or present with life-threatening complications. Pathophysiology Liver infarction is caused by sudden interruption of hepatic arterial flow in combination with predisposing factors. Interruption of the hepatic arterial flow by itself generally does not lead to liver infarction because the liver has a dual blood supply and a rich peribiliary arterial collateral network. Retrograde filling from the portal veins or peribiliary collaterals may sustain the liver parenchyma if arterial flow is interrupted. Interruption of the hepatic arterial flow may be caused by luminal obstruction (thrombosis, embolism, arterial spasm) or global hypoperfusion (shock). His predisposing condition was partial thrombosis of the superior mesenteric artery and replaced right hepatic artery supplying the right liver lobe. Notice the preserved portal tracts with a normal course of hepatic vessels traversing the area. A coronal reformatted image (C) shows the replaced right hepatic artery arising from a partially thrombosed superior mesenteric artery (arrow). Multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma or diffuse metastatic disease: Difficult to differentiate from multiple infarcted regenerative nodules. History of cirrhosis, episode of hypotension, and rapid development of lesions compared with recent comparison studies, if available, may suggest the correct diagnosis. Key Points Rare, usually occurs after interruption of hepatic arterial supply in combination with one or more predisposing conditions. Management/Clinical Issues Early infarction may be reversible if sufficient arterial perfusion is established. This may occur owing to spontaneous resolution of the arterial obstruction or by a revascularization procedure. Multifactorial aetiology of hepatic infarction: a case report with literature review. Bland Thrombosis Definition Bland portal vein thrombosis is a benign acquired occlusion of the main portal vein or its branches due to intraluminal thrombus formation. Pylephlebitis, also known as infective suppurative thrombosis of the portal vein, is bland portal vein thrombosis caused by septic seeding. Cavernous transformation involves the formation of multiple tortuous collateral vessels in and around an occluded portal vein. Demographic and Clinical Features Portal vein thrombosis can be caused by stagnant flow (often in the setting of cirrhosis with preexisting portal hypertension), hypercoagulable state, adjacent inflammation (pancreatitis, duodenitis), or infection with septic seeding of the portal vein (pylephlebitis). Common sources of infection are appendicitis, diverticulitis, and inflammatory bowel disease. Portal vein thrombosis may also occur as a complication of liver transplantation or catheterization. Cirrhosis is the most frequent predisposing disorder in adults, while infection is the most frequent predisposing disorder in children. In patients with underlying cirrhosis, bland portal vein thrombosis is usually clinically silent, since the clinical picture is dominated by the preexisting portal hypertension and underlying liver disease. In patients without underlying cirrhosis, bland portal vein thrombosis is usually asymptomatic in the acute phases. Abdominal pain may result from intestinal ischemia if the thrombosis extends into the superior mesenteric vein. Chronically, bland portal vein thrombosis presents with portal hypertension and its sequelae, such as splenomegaly, variceal and gastrointestinal hemorrhages, and ascites. Chronic bland portal vein thrombosis in patients without underlying cirrhosis is a leading cause of presinusoidal portal hypertension.

© 2025 Adrive Pharma, All Rights Reserved..