General Information about Plavix

Plavix is a life-saving treatment that has helped hundreds of thousands of individuals worldwide to reduce their danger of coronary heart assault, stroke, and other circulation issues. It is an important medication for patients with a high risk of developing blood clots and is an important part of their therapy plan. However, it is important to observe your physician's instructions and take necessary precautions whereas taking Plavix to ensure its effectiveness and minimize the chance of side effects.

Plavix is a type of drug referred to as P2Y12 inhibitors that blocks the ADP receptors on the platelets, preventing them from clumping collectively and forming clots. By doing so, Plavix helps to maintain a healthy blood circulate, reducing the risk of heart assault and stroke.

Every treatment has the potential risk of unwanted aspect effects, and Plavix isn't any exception. Though not everyone experiences them, some patients might experience gentle signs such as nausea, indigestion, diarrhea, headache, and bruising simply. However, in some rare cases, Plavix might trigger severe side effects such as bleeding, allergic reactions, and liver issues. It is essential to consult your physician should you experience any uncommon symptoms while taking Plavix.

Plavix is on the market in the form of an oral pill and is usually taken once a day, with or with out food. The usual dosage for adults is 75mg daily, but it can differ depending on the affected person's medical historical past and condition. It is essential to observe your doctor's directions and take the medication exactly as prescribed to make sure its effectiveness.

Possible Side Effects

Who Needs Plavix?

In Conclusion

The Science Behind Plavix

Plavix may also interact with certain medications similar to blood thinners, NSAIDs, and proton pump inhibitors. It is essential to tell your physician about all the medications you are taking earlier than starting Plavix to avoid any potential interactions.

Plavix is a extensively prescribed medication used to forestall the formation of blood clots in sufferers who are at a higher threat of growing circulation problems, stroke, and coronary heart assault. It is a life-saving drug that has been helping hundreds of thousands of individuals worldwide to reduce back their threat of cardiovascular disease.

Moreover, Plavix is prescribed to patients with a history of blood clots in their legs or lungs, to stop them from recurring. Patients with a household historical past of heart disease or those that smoke, have excessive cholesterol, or have diabetes are also often prescribed Plavix as a safety measure.

Precautions and Interactions

Plavix is prescribed to individuals who have a higher danger of growing blood clots due to underlying health circumstances corresponding to coronary artery disease, peripheral artery illness, and a past history of heart assault or stroke. It is also recommended for sufferers who have undergone certain medical procedures such as coronary stenting or coronary heart bypass surgical procedure.

How to Take Plavix

Plavix is usually a secure and effective medicine; nevertheless, it is important to take sure precautions whereas taking it. Since Plavix can enhance the danger of bleeding, it's imperative to keep away from activities that can cause damage. If you are experiencing any bleeding or present process surgery, it's essential to tell your doctor about your Plavix treatment.

Plavix, additionally known by its generic name Clopidogrel, is an oral antiplatelet treatment that works by stopping the platelets within the blood from sticking collectively. Platelets are tiny cells within the blood that kind clots to cease bleeding when a blood vessel is broken. However, in some instances, these blood clots can kind inside the blood vessels, causing blockages and stopping blood flow to very important organs. This can lead to severe health situations such as heart assault, stroke, and different circulation issues.

As the object is being removed pre hypertension lifestyle changes cheapest generic plavix uk, the speculum or anoscope should be removed along with it so that the foreign body does not have to fit through these instruments. With an object that is too high to reach, the patient can be admitted and sedated for removal over the next 6 to 12 hours. When the object cannot be removed because of patient discomfort or sphincter tightness, removal must be accomplished in the operating room under spinal or general anesthesia. When blood is present in the rectum, when pain is severe or persistent, when there is fever or rectal discharge, or when the object is capable of doing harm to the bowel, proctoscopic evaluation should be performed after removal of the foreign body to rule out rectal injury. When pain persists or there is any lingering suspicion of a bowel perforation, keep the patient for 24 hours of observation and consider performing a water-soluble contrast enema study. Do not attempt to remove a rectal foreign body in a patient who is having severe abdominal pain or who has signs of a bowel perforation. Do not attempt to remove fragile or sharp, jagged objects, such as broken glass, through the rectum. Do not attempt to remove packets of illicit drugs with clamps or sharp medical instruments, because spillage can lead to toxicity and death. Admit him and observe for peritoneal signs, increased pain, fever, and a rising white blood cell count. Discussion Anorectal foreign bodies can be either ingested orally or inserted anally. Although the vast majority are inserted for autoerotic purposes, they may have been placed iatrogenically or as a result of assault or trauma. Objects placed as a result of assault, trauma, or eroticism represent a diverse collection, including sex toys; tools; wire hangers and instruments; bottles, cans, and jars; poles, pipes, and tubing; fruits and vegetables; stones; balls; balloons; light bulbs; and flashlights. Most of these rectal foreign bodies can be removed safely in the emergency department or acute care clinic. Relaxation is essential, and sedation is usually necessary if retrieval is to be successful. Some practitioners quite reasonably forgo radiographs before manipulation if the patient is free of pain and fever and if the object is benign. Stridor or dyspnea resulting from tracheal compression may occur in young children. Disturbed or cognitively impaired adults may be brought from mental health facilities to the hospital on repeated occasions, at times accumulating a sizable load of ingested material. Impacted esophageal foreign bodies are more likely to cause the symptoms described, whereas gastric foreign bodies are usually asymptomatic. Ask capable patients about their symptoms and examine them, looking for signs of airway obstruction. In small children, this should include the area from the nasopharynx to the upper abdomen, which can often be done with a single large radiographic plate. A coin located in the proximal esophagus will be oriented in the coronal plane on an anteroposterior projection. Button batteries, which can be hazardous, can be differentiated from a simple coin by their "double ring" appearance on radiographs. Many foreign bodies are radiolucent; therefore a negative radiograph does not rule out a foreign body. Examples include toothpicks, medication blister packs, open safety pins, toothbrushes, plastic bag clips, and elongated nails and wires. Toothpicks are shorter than this, but they are associated with a high incidence of perforation. Plastic bag clips have a propensity to attach to the folds of the small bowel with subsequent small bowel ulceration and the potential for hemorrhage, perforation, and healing with fibrosis and obstruction. If this is unsuccessful, consult with the parents, along with a pediatric endoscopist, regarding further observation for up to 24 hours as an outpatient or inpatient, or possibly performing endoscopic removal as soon as possible. When a coin or other smooth object has been lodged in the upper esophagus of a healthy asymptomatic child for less than 24 hours, and endoscopy is not readily available and the parents are supportive about avoiding general anesthesia, the object can often be removed using a simple Foley catheter technique. When available, this can be performed under fluoroscopy; although, to avoid this radiation, it can be safely performed as a blind procedure. Test the balloon of an 8- to 12-Fr Foley catheter to ensure that it inflates symmetrically. Inflate the balloon with 5 mL of air and apply gentle traction on the catheter until the foreign body reaches the base of the tongue. When removal is successful, repeat the radiograph to be sure that there are no additional coins, and discharge the patient after a brief period of observation. Also, when there is parental support, esophageal bougienage is a safe, effective, and inexpensive method to advance coins or smooth objects from the distal esophagus in to the stomach without sedation. After topical anesthesia of the throat, wrap the patient in a bed sheet with arms at the side and have an assistant hold the child upright. Advance a well-lubricated, blunt, round-tipped Hurst-type esophageal dilator through the mouth and esophagus in to the stomach, then remove it. Dilator size should be 28 Fr for ages 1 to 2, 32 Fr for ages 2 to 3, 36 Fr for ages 3 to 4, 38 Fr for ages 4 to 5, and 40 Fr for those older than 5 years of age. These two rapid, simple, cost-effective techniques have been shown in the past to be safe and effective. It is for this reason that Foley catheter manipulation and bougienage are not recommended for coins that have been entrapped for more than 24 hours. Children with distal esophageal coins may be safely observed up to 24 hours before an invasive removal procedure, because most will spontaneously pass the coins. For potentially hazardous radiopaque objects, repeat radiographs every 3 to 4 days to confirm that passage of the object is necessary.

In malignant mesenchymal tumours the suffix becomes sarcoma; thus a liposarcoma is a malignant neoplasm of fat blood pressure medication pril order 75 mg plavix overnight delivery, and an angiosarcoma is a malignant neoplasm of blood vessels (or, more strictly speaking, endothelium). Lymphoreticular neoplasms All neoplasms derived from lymphocytes are referred to as lymphomas, with the exception of those that circulate, which are referred to as leukaemias. Broadly speaking, they can be subdivided in to lymphomas of B lymphocytes or T lymphocytes and high-grade or low-grade lesions, the latter distinction being the most important for management and prognosis. More recently, certain types of lymphomas have become more strictly defined by cytogenetic or molecular genetic abnormalities. For example, mantle cell lymphoma is a type of B cell lymphoma with morphology similar to low grade lymphomas but with a more aggressive clinical course. The vast majority of tumours occurring in the nervous system are derived from support tissues. In the central nervous system these are most commonly astrocytomas; in the peripheral nervous system they are derived from Schwann cells or nerve sheath fibroblasts, which form Schwannomas and neurofibromas, respectively. Although they are usually sporadic and single, these benign nerve sheath tumours are notable for sometimes being multiple in the setting of the familial syndromes of neurofibromatosis type 1 (multiple neurofibromas) and type 2 (acoustic Schwannomas, meningiomas and ependymomas). An important concept that is illustrated by tumours of the central nervous system is the distinction between histological and biological malignancy. A non-invasive cerebral neoplasm acts as a space-occupying lesion and, therefore, has the potential to kill the patient, although it may do this over a longer period of time than its histologically malignant counterparts. Neoplasms of nervous tissue Mature nerve cells very rarely give rise to any type of neoplasm; however, their precursors can give rise to a variety of tumours such as neuroblastoma and medulloblastoma. These are examples of a variety of neoplasms bearing the suffix blastoma which are derived from embryonal cells and occur almost exclusively in children. These neoplasms can be benign or malignant, and are characterised by their ability to secrete peptide hormones or vasoactive amines. They usually present with symptoms caused by the substance that they secrete rather than symptoms directly attributable to the tumour itself. The resultant syndromes will be discussed in more detail in the section below on clinical effects. However, it is common practice to refer to tumours secreting an identifiable product as causing a distinct syndrome according to their product, for example, insulinoma or gastrinoma; others are referred to by the generic term carcinoid. These tumours are generally of low to intermediate grade malignancy; their highly malignant counterpart is the so-called small cell carcinoma. These are often congenital and may thus be hamartomas rather than true neoplasms (this distinction will be explained below), although others may be acquired in childhood or adulthood. Mixed neoplasms A number of neoplasms show more than one neoplastic component, most commonly both epithelial and mesenchymal, indicating origin from a cell capable of differentiating down both lineages. This is distinct from the recruitment of non-neoplastic stroma that occurs in most epithelial neoplasms (see section on tumour dependency). Examples of benign mixed neoplasms are the fibroadenoma of the breast and the so-called pleomorphic salivary gland adenoma. Malignant neoplasms consisting of a mixture of epithelial and mesenchymal elements are generally referred to as carcinosarcomas; these occur most commonly in the female genital tract. There are some examples of mixed tumours which are distinctive clinicopathological entities such as synovial sarcoma (a misnomer because it is not derived from synovium) and the so-called pulmonary blastoma. Germ cell neoplasms Like other cell types, spermatogonia and oocytes are capable of forming neoplasms. Although germ cells themselves are haploid, the neoplasms that arise from them are generally diploid. The capacity of these cells to differentiate down the various embryonic lineages determines how germ cell neoplasms can manifest themselves. The degree of differentiation of a teratoma is reflected in the maturity of the tissues it forms. The maturity of teratomas dictates their behaviour: mature teratomas occurring in females are common and benign, whereas immature teratomas are uncommon and malignant. In males, teratomas of any type can give rise to metastases, although the more immature types are usually more aggressive. In mature cystic teratomas, well-formed squamous epithelium, glandular epithelium, neural tissue and teeth are frequently seen and almost any other tissue can be present. Other related tissues such as yolk sac and trophoblast may also be present in immature teratomas. The majority of germ cell tumours arise in the gonads, but some arise in sites such as the mediastinum and retroperitoneum, reflecting the site of origin and path of migration of the primordial germ cells. The majority of teratomas in females are mature; in males the majority are immature. Malignant germ cell tumours are far more sensitive to radiotherapy and chemotherapy than, for example, malignant epithelial neoplasms. This has resulted in an excellent prognosis for seminomas and a relatively good prognosis for teratomas, even when metastatic disease is present. A related group of neoplasms are the gestational trophoblastic tumours which are derived, as their name indicates, from placental trophoblast following a pregnancy. They are very uncommon following normal pregnancies, but are relatively more common following (hydatidiform) molar pregnancies. Like normal trophoblast, the cells of these tumours are well equipped to invade and metastasise, but are fortunately highly sensitive to chemotherapy. Poorly differentiated neoplasms A proportion of malignant neoplasms do not show any evidence of differentiation, by conventional light microscopy. However, advances in electron microscopy and more particularly immunohistochemstry and cytogenetics now allow the majority of these neoplasms to be at least assigned to a broad category such as lymphoma or carcinoma, and sometimes to be diagnosed precisely. These distinctions can be of great importance to patient management: for example, an undifferentiated tumour that on further investigation proves to be a lymphoma may be highly responsive to appropriate chemotherapy.

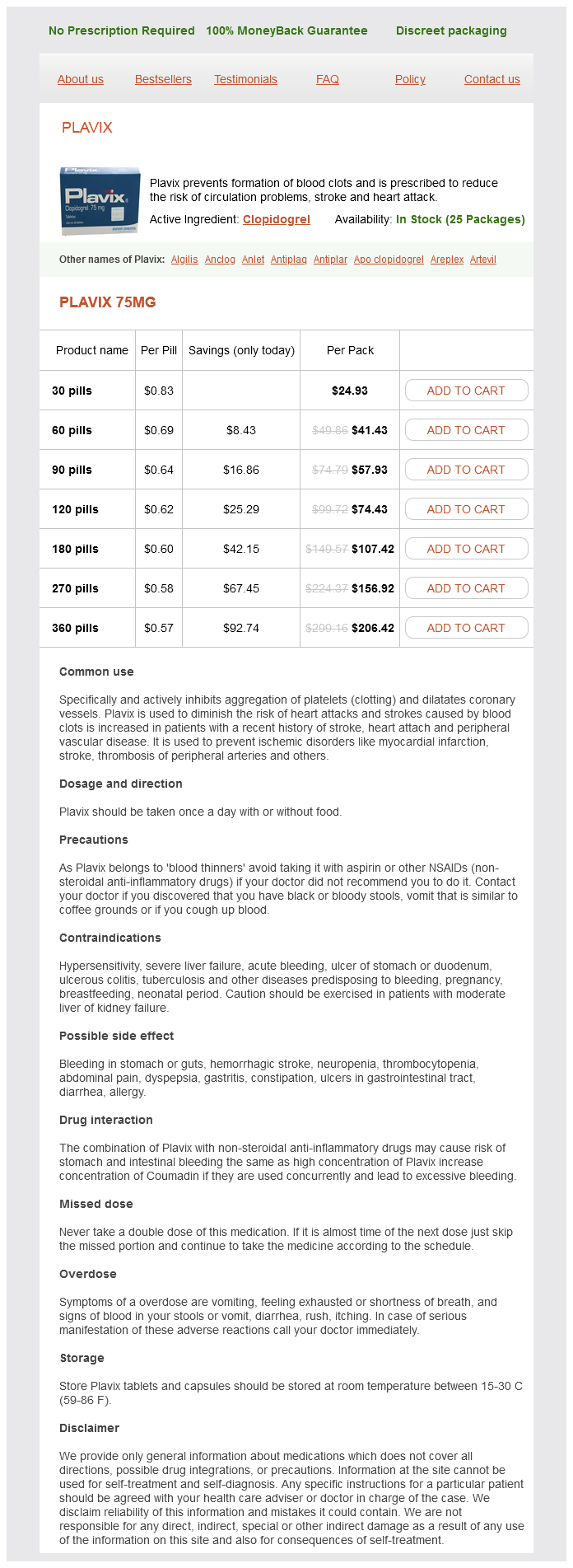

Plavix Dosage and Price

Plavix 75mg

- 30 pills - $24.93

- 60 pills - $41.43

- 90 pills - $57.93

- 120 pills - $74.43

- 180 pills - $107.42

- 270 pills - $156.92

- 360 pills - $206.42

It starts at the aortic valve and goes up and slightly to the right heart attack 3 28 demi lovato heart attack single pop order genuine plavix on-line, ending to the right of the sternum at the level of the second right costal cartilage. Relations On the left anterior surface the aortic arch is crossed by: Branches the left and right coronary arteries are the only branches; these have already been described on pages 230 and 231. It ends in the midline at the lower border of the 12th thoracic vertebra, where it passes behind the median arcuate ligament of the diaphragm. Lateral segmental branches these are the posterior intercostal arteries that supply the lower nine of the eleven intercostal spaces. The blood supply to the cord consists of the anterior and posterior spinal arteries, which descend in the pia from the intracranial part of the vertebral artery. They are reinforced by segmental arteries, and in the thoracic region these are the dorsal branches of the 2nd to 11th posterior intercostal arteries. These supply the radicular arteries to the spine, which are a very important contribution to reinforce the longitudinal vessels. The largest one is known as the arteria radicularis magna (or artery of Adamkiewicz), which most commonly arises at the 10th or 11th thoracic level but may arise anywhere up to the 4th thoracic level. Operations on the thoracic spine or thoracic aneurysms may interfere with the parent stems of these radicular vessels, which may result in damage to the spinal cord, causing paraplegia. Lateral visceral (bronchial) these supply the bronchial walls and substance of the lung excluding the alveoli. Relations Anteriorly are the root of the lung, the pericardium of the left atrium, and below that the posterior fibres of the diaphragm. Anteriorly and to the right lie the oesophagus and trachea; lower down the oesophagus becomes anterior and then moves to its left as it descends. Posteriorly are the vertebral column and hemiazygos veins, to the right are the azygos veins and thoracic duct and pleura and lung, and on the left the pleura and lung. Branches Posterior lateral branches to the body wall There are five-paired branches: the inferior phrenic artery and four lumbar arteries. Paired to viscera There are three-paired visceral arteries: the suprarenal, the renal arteries and the testicular or ovarian arteries. Midline unpaired branches to the viscera There are three such branches, as follows: · · · the coeliac trunk supplies the foregut and its derivatives which are the stomach, duodenum, liver, gallbladder and part of the pancreas. The coeliac trunk arises from the aorta, immediately below the aortic opening in the diaphragm. Inferior mesenteric artery supplies the hindgut from the left third of the transverse colon down to the rectum, where it terminates as the superior haemorrhoidal arteries. It arises from the lower third of the abdominal aorta, and is a much smaller artery than the coeliac and the superior mesenteric. It anastomoses with the superior mesenteric via the marginal artery (see Chapter 17). Relations To the right from above downwards are the right crus of the diaphragm, the cisterna chyli and the commencement of the azygos vein. To the left is the left crus of the diaphragm, the fourth part of the duodenum, the duodenojejunal flexure and the left sympathetic trunk. Anteriorly at the level of the coeliac trunk, the lesser sac of peritoneum separates the aorta from the lesser omentum and liver. Below that, the left renal vein crosses the abdominal aorta immediately below the origin of the superior mesenteric artery. This is at the level of the neck of the vast majority of abdominal aortic aneurysms. It is usually possible to get a clamp on just below the renal vein, but occasionally the aneurysm extends high up, stretching the renal vein like a ribbon across it. Because the left renal vein has tributaries from the left adrenal and from the left ovarian or testicular, the left renal vein can be divided providing it is sufficiently far to the right not to impair the entrance of these vessels, which can then act as venous collaterals. In an elective aneurysm this is not a problem, but when there is a large haematoma following a leak, it is possible to damage it if one is not aware of its presence. Also the third part of the duodenum may be adherent to an aneurysm, which may be a particular problem if it is an inflammatory aneurysm. When the anastomosis between a graft and aorta has been done, it is important to have some tissue between it and the duodenum (usually the wall of the aneurysm sac is used). If this is not done there is a small risk of a fistula developing between the anastomosis and the duodenum (aortoduodenal fistula) which is an uncommon but serious cause of haematemesis and melaena. The pancreas lies anterior to the aorta with the third part of the duodenum below. Below this lie the parietal peritoneum and peritoneal cavity with the line of attachment of the mesentery to the small bowel. These vessels are thus at risk, for example, when inserting a needle to obtain a pneumoperitoneum. It is also worth noting that the bifurcation of the aorta is approximately at the level of the umbilicus, so that aneurysms of the abdominal aorta are normally above this level (although they may, of course, involve the common iliacs). In addition there are the pulmonary trunk, right and left pulmonary arteries and the four pulmonary veins which are the great vessels of the pulmonary circulation (see Chapter 11). The brachiocephalic artery this is the first and largest of the three great arteries arising from the aortic arch. There are normally no branches, though occasionally the thyroidea ima artery may arise from it, supplying the lower part of the thyroid. It arches laterally over the apex of the lung to reach the superior surface of the first rib, where it lies in a groove just behind the insertion of the scalenus anterior. This artery is clinically important, because it can be used for coronary artery bypass grafts by mobilising it and anastomosing it directly to the coronary arteries beyond a stenosis or block.

© 2025 Adrive Pharma, All Rights Reserved..