General Information about Fincar

Fincar has been scientifically confirmed to assist forestall further hair loss and promote hair re-growth in males affected by male pattern hair loss. In a five-year clinical examine, 9 out of 10 males who took Fincar daily skilled an increase in hair development and a slowdown in hair loss. Furthermore, 48% of the lads who participated in the examine showed visible hair regrowth after one year of utilizing Fincar.

It is worth noting that Fincar is not a remedy for hair loss, and it have to be taken repeatedly to take care of its effects. If treatment is stopped, any hair regrowth might be lost within 12 months, and hair loss will continue as it will have, had the treatment never been started. Therefore, Fincar must be used as a long-term treatment for male sample hair loss.

Fincar is a safe and well-tolerated medication, and if taken as directed, the side effects are typically delicate and rare. However, like all medications, Fincar could cause sure unwanted facet effects in some men. The mostly reported unwanted effects of Fincar include a decrease in libido, erectile dysfunction, and a decrease in ejaculate volume. These unwanted effects are often mild, they usually disappear as soon as the medicine is discontinued. In uncommon circumstances, some men could experience breast enlargement or breast tenderness, but these unwanted facet effects often resolve on their very own without intervention.

One major concern about Fincar, and any medicine that affects hormones, is its potential impact on fertility. Some research have shown that Fincar can lower sperm rely and motility, however this effect is reversible once the treatment is discontinued. Nonetheless, men who're making an attempt to conceive ought to seek the assistance of with their doctor before beginning Fincar or some other treatment that impacts hormones.

Fincar, also referred to as finasteride, is a well-known treatment used for treating male sample hair loss. While hair loss is frequent and might affect folks of all ages, it's extra prevalent in males. Male sample hair loss, also called androgenetic alopecia, is a genetic condition that can be hereditary and might occur at any age after puberty. It is estimated that by the age of 50, over 50% of men will experience some degree of hair loss.

In conclusion, Fincar is a broadly used and efficient treatment for male sample hair loss. It works by lowering the degrees of the androgen hormone, which is liable for hair loss in men. While unwanted aspect effects are uncommon and often delicate, Fincar should be taken as directed to take care of its beneficial results. Men who are experiencing hair loss ought to speak to their physician about Fincar as a potential therapy option. With its confirmed efficacy and safety report, Fincar can help men regain their self-confidence and improve their total well-being.

In latest years, Fincar has gained reputation as a remedy for male pattern hair loss. Developed by Merck & Co., Fincar has been approved by the us Food and Drug Administration (FDA) since 1997 to be used in males only. It is available in pill form and is taken orally once a day. The energetic ingredient in Fincar is finasteride, which works by inhibiting the manufacturing of the male hormone, androgen. Androgens, also called male hormones, play a job in hair loss, and Fincar works by decreasing the levels of dihydrotestosterone (DHT), a potent form of androgen responsible for hair loss in men.

Neurochemical profile of glioneuronal lesions from patients with pharmacoresistant focal epilepsies prostate cancer gene order generic fincar on-line. Alterations of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway components in epilepsy-associated glioneuronal lesions. Frequency of seizures in patients with newly diagnosed brain tumors: a retrospective review. Expression of connexin 43 and connexin 32 gap-junction proteins in epilepsy-associated brain tumors and in the perilesional epileptic cortex. Epilepsy in patients with brain tumours: epidemiology, mechanisms, and management. Oxcarbazepine monotherapy in patients with brain tumor-related epilepsy: open-label pilot study for assessing the efficacy, tolerability and impact on quality of life. Seizure recurrence and risk factors after antiepilepsy drug withdrawal in children with brain tumors. First-line nitrosourea-based chemotherapy in symptomatic non-resectable supratentorial pure low-grade astrocytomas. Electro-clinical characteristics and postoperative outcome of medically refractory tumoral temporal lobe epilepsy. Medically refractory epilepsy associated with temporal lobe ganglioglioma: characteristics and postoperative outcome. P450 enzyme inducing and non-enzyme inducing antiepileptics in glioblastoma patients treated with standard chemotherapy. Pharmacotherapy of epileptic seizures in glioma patients: who, when, why and how long Retrospective analysis of the efficacy and tolerability of levetiracetam in brain tumor patients. Retrospective analysis of the efficacy and tolerability of levetiracetam in patients with metastatic brain tumors. Levetiracetam monotherapy in patients with brain tumor-related epilepsy: seizure control, safety, and quality of life. This is of particular relevance when discussing seizures occurring in the context of systemic diseases and where they should fit in such a classification. Seizures in systemic diseases are not an inconsiderable problem, especially in the critically ill. The currently used terms, acute and remote symptomatic seizures (as differentiated by the temporal relationship to the provoking factor), are confusing and probably too simplistic as most seizures occurring in systematic disease are likely to be multifactorial, even if one cause predominates. In a recently proposed aetiological classification of epilepsy (3), epilepsy is divided into four broad categories: idiopathic, symptomatic, provoked, or cryptogenic epilepsy. Estimating the true frequency of seizures in people with primarily non-neurological conditions is difficult as this has rarely been subject to systematic examination. Nevertheless it does seem that seizures are one of the more common neurological manifestations of systemic disease. Seizures arising as a consequence of systemic disease can be convulsive or non-convulsive, focal or generalized (either primary or secondary generalized), and particularly status epilepticus (convulsive and non-convulsive), the majority of which occurs in people with no prior history of epilepsy (5). A high index of suspicion for the possibility of subtle convulsive or non-convulsive status epilepticus as well as the possibility of non-epileptic seizures needs to be maintained in the critical care setting. In this chapter, we will primarily deal with what are termed situation-related seizures and as such the seizures can be explained by the provoking circumstances. Pathophysiology of seizures in systemic diseases Any critically ill person can develop seizures if the provoking stimulus is severe enough to lower their seizure threshold sufficiently, much the same as people with epilepsy may experience an exacerbation in their seizure control in the context of concurrent illness. Nevertheless, the systemic insult required to provoke seizures is much greater in people without a prior history of epilepsy. Electrolyte imbalances such as sodium, glucose, calcium, magnesium, and, rarely, low levels of potassium, can affect neuronal excitability and are important precipitants of seizures in the critically ill. Seizures as a consequence of electrolyte disturbances typically occur in the context of encephalopathy, drowsiness, headache, stupor, and other neurological symptoms (6). Similarly, disturbances in the balance of neurotransmitters can predispose to seizures such as depletion of the inhibitory neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid or accumulation of excitatory amino acids such as glutamate and aspartate which occurs after hypoxicischaemic brain injury, leading to increased neuronal excitability and neuronal damage (7). People with chronic renal failure are at increased risk of cerebrovascular disease (both ischaemic and haemorrhagic strokes), which is a significant risk for the development of subsequent seizures particularly in the elderly. Sixty per cent of seizures were single seizures with few of the remaining children developing long-term seizures. The main aetiological factor was hypertension with seizures often heralding onset of hepatic encephalopathy. The majority of people with seizures did not a recurrence of seizures following control of hypertension (19). In a series of 119 renal transplants in 109 children over a 10-year period, 20 children (17. Seizures occurred within 8 weeks of transplantation in 13 (62%) and within 6 months in 18 (85. Of the seizures in the 21 transplant patients, 13 (62%) were single seizures, nine children experienced multiple seizures, and one child had status epilepticus. The risk of seizures post transplant was not significantly different between the two groups (p = 0. The most commonly identified aetiology for the development of seizures was hypertension (15 (71. Overall the long-term prognosis was very good with only five children requiring long-term Seizures in renal disease Seizures are one of the most common manifestations of neurological dysfunction in uraemic encephalopathy which can occur in either acute or untreated chronic renal failure, either as a direct consequence of the condition itself or as a complication of its treatment, or both. Depending on the rapidity of the onset and degree of renal failure, people with uraemic encephalopathy present with headaches, irritability, fluctuating levels of consciousness, seizures (epilepsia partialis continua, convulsive and non-convulsive status epilepticus), coma and death (8). The precise pathophysiology of uraemic encephalopathy is poorly understood but an accumulation of metabolites, hormonal disturbance, imbalance in inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmitters and disturbance of the intermediary metabolism have all been postulated as potential contributing factors (8). It has been estimated that one-third of people presenting with uraemic encephalopathy have seizures, sometimes as the initial symptom (9, 10).

The seizing patient should nevertheless be protected from falling and injury prostate 71 order generic fincar on line, and be turned towards the recovery position as soon as the convulsion stops, for the period of the postictal state to resolve. Facing a subject experiencing a partial-complex seizure (or a confusional postictal state without deep consciousness impairment), it is helpful to bear in mind that attempts at restraint may result in an untargeted, defensive, but at time aggressive behaviour from the patient. Discussion of targeted treatment towards the aetiology of seizures in this situation is beyond the scope of this chapter, but should receive full attention as it probably represents the best prevention from seizure recurrence. Patients with at least a putative diagnosis of epilepsy, and not only of provoked seizures, should be considered for a long-term treatment. Status epilepticus at presentation bears a three times higher risk of seizure recurrence as compared to a short seizure (53). If a first seizure occurs during sleep, the recurrence risk appears greater compared to episodes arising from wakefulness (48, 54, 55), although this tendency may be in part explained by the possibility of the prior occurrence of unrecognized and undiagnosed seizures during sleep (49). Descriptive epidemiology of epilepsy: contributions of population-based studies from Rochester, Minnesota. Repeated ambulance use by patients with acute alcohol intoxication, seizure disorder, and respiratory illness. The borderland of epilepsy: clinical and molecular features of phenomena that mimic epileptic seizures. Emergencies in parkinsonism: akinetic crisis, life-threatening dyskinesias, and polyneuropathy during L-Dopa gel treatment. Clinical course and variability of non-Rasmussen, nonstroke motor and sensory epilepsia partialis continua: A European survey and analysis of 65 cases. Psychogenic seizures: A review and description of pitfalls in their acute diagnosis and management in the emergency department. While the recurrence rate at 2 years was 50% lower in the treated group (46), the chance of a 5-year remission at 10 years was identical (64% in both arms) (56). Similar thoughts may apply for adults, also in view of the risk of discrimination and stigma related to epilepsy. On the other hand, regulatory implications on the quality of life, especially regarding driving, may affect the decision in this age group. As opposed to patients having seizures provoked by reversible causes, which do not need a specific treatment, those experiencing a first seizure due to an acute aetiology that may, in part, endure. There is, however, no evidence that continuing treatment on a long-term basis, in the absence of clear evidence of an increased risk of recurrence, is beneficial. Do observer and self-reports of ictal eye closure predict psychogenic nonepileptic seizures Postictal breathing pattern distinguishes epileptic from nonepileptic convulsive seizures. Outcome in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: 1 to 10-year follow-up in 164 patients. Bilateral tonic-clonic seizures with temporal onset and preservation of consciousness. Diagnosis of psychogenic nonepileptic status epilepticus in the emergency setting. Practice Parameter: evaluating an apparent unprovoked first seizure in adults (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Interictal spiking increases after seizures but does not after decrease in medication. Use of serum prolactin in diagnosing epileptic seizures: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. The diagnosis and management of seizures and status epilepticus in the prehospital setting. Value of clinical features, electroencephalography, and computerised tomographic scanning in prediction of seizure recurrence. Predictors of multiple seizures in a cohort of children prospectively followed from the time of their first unprovoked seizure. Treatment of the first tonic-clonic seizure does not affect long-term remission of epilepsy. Epilepsy and other chronic convulsive disorders: their causes, symptoms and treatment. Practice parameter: treatment of the child with a first unprovoked seizure: Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Hypotension, acidosis, hyper/hypoglycaemia, and hyperpyrexia increase acute morbidity, long-term morbidity, and mortality (13). At the same time the bloodbrain barrier is progressively disrupted with increased protein in the cerebrospinal fluid (3, 5, 6). It might be surmised that with the advancement of neurocritical care and intensive care medicine in particular, these figures (but especially the mortality rate directly linked to the status itself/to intensive care management) will improve (9, 10). In a series of 94 head trauma victims, 11 had subclinical seizures, six of these 11 patients were in subtle generalized convulsive status, all of them eventually died (10). History taking, physical examination, and primary laboratory examinations (blood gas analysis, blood glucose) must be completed rapidly (5). Neuromuscular blockade should not be given in these patients; however, if absolutely necessary, vecuronium 0. Pentobarbital 515 mg/kg body weight over 1 hour (or thiopental 37 mg/kg/hour), then continue pentobarbital 0. Monitoring must be on high alert to recognize any incipient nosocomial infection (regular culturing of body fluids, regular C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, white blood cell count, etc.

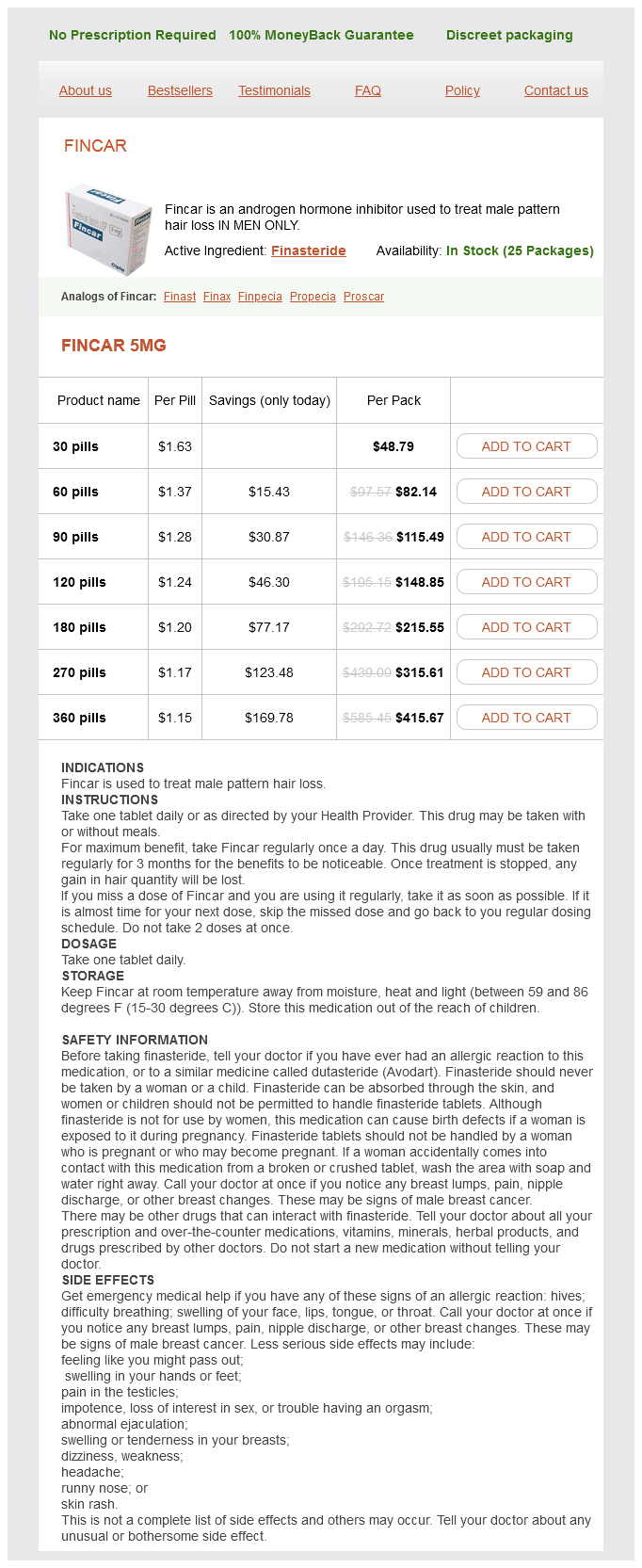

Fincar Dosage and Price

Fincar 5mg

- 30 pills - $48.79

- 60 pills - $82.14

- 90 pills - $115.49

- 120 pills - $148.85

- 180 pills - $215.55

- 270 pills - $315.61

- 360 pills - $415.67

Weight change and antiepileptic drugs: health issues and criteria for appropriate selection of an antiepileptic agent prostate cancer 3 plus 3 best purchase for fincar. Does the cause of localisation-related epilepsy influence the response to antiepileptic drug treatment Therapy in this situation is less likely to be successful than in newly diagnosed epilepsy, and there are several alternative theories about why this might be so. It has been suggested, for instance, that the longer epilepsy remains active, the more resistant it becomes to treatment due to the many molecular changes that occur in ongoing epilepsy. Alternatively, it is possible that the difference is due simply to selection and that patients with chronic epilepsy comprise the inherently more severe forms of the condition which is unresponsive to therapy from the very start of therapy when compared to the milder epilepsies where seizures are controlled at the onset of therapy. The goal of drug therapy in newly diagnosed cases is the complete control of seizures, and this occurs in about 6070% of patients within a few years of the onset of the condition (26). This leaves 3040% of patients who continue to have seizures, and thus develop chronic epilepsy. Treatment in chronic epilepsy is more complex and more difficult than in the newly diagnosed epilepsy. However, long-term seizure control in patients with chronic epilepsy can be obtained, with skilful treatment, in about 30%, and it should be further possible to greatly lessen the frequency or severity of seizures in many of those in whom complete control is not possible. There remain about 10% of all those developing epilepsy in whom seizures remain severe, frequent, or intractable. Factors associated with chronicity include: high seizure density prior to commencing treatment, certain epileptic syndromes, certain aetiologies, the presence of additional learning disability, neuropsychological signs, or neurological signs, psychological disturbance (68). The additional learning disability, psychosocial problems, or other neurological handicaps which coexist with chronic epilepsy can complicate medical therapy further. Chronic epilepsy can have a major impact on an individual, impacting on personal and domestic life, employment, and education (9). This chapter focuses on the principles of drug therapy in chronic epilepsy, although it must be emphasized that drug therapy is only part of a treatment strategy which should also include counselling, lifestyle manipulation and avoidance of provoking factors, and non-pharmacological therapy. The special aspects of therapy in children, persons with learning disability, and in the elderly are covered elsewhere (Chapters 1618). Choice of antiepileptic drug therapy in chronic epilepsy In chronic epilepsy, the choice of drug will be usually largely independent of the cause of epilepsy. The overall chance of effecting seizure control is similar for individual drugs, at least in the generality of partial and secondarily generalized epilepsy, but side effects vary more, and the choice of drugs is often more influenced by relative tolerability than efficacy (11). This lack of specificity applies to tonicclonic and partial-onset seizures, which are the most common forms of epilepsy in adults, but not to other seizure types, which are much less common, nor to the specific childhood syndromes discussed in Chapter 16. Seizure type and the choice of antiepileptic drugs the usual choices of drugs in different seizure types can be summarized under four categories (Table 23. Generalized tonicclonic and partial onset seizures A wide range of drugs are licensed for use in tonicclonic or partialonset seizures in chronic epilepsy, whether primarily or secondarily generalized (1214). A number of drugs are licensed for use in monotherapy, including: carbamazepine (best used in its slow-release formulation), lamotrigine, valproate, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, or topiramate (15, 16). The other drugs, which are licensed as add-on therapy, are used as second-line therapy. The older drugs, phenobarbital and phenytoin, are also used as first-line therapy in some countries. A number of comparative studies have been carried out, but no one first- or second-line drug has been found to be consistently 254 oxford textbook of epilepsy and epileptic seizures Table 23. However, the similarity in overall antiepileptic effects hides important individual differences, both in side-effects and in efficacy, and there are many patients who fail to respond to one drug but who do respond to another. It is therefore usual, and indeed logical, to rotate a patient through trials of treatment with all appropriate therapies (17). In partial-onset seizures, it is also frequently stated that carbamazepine is more effective than valproate, but again there is little or no definitive evidence of such a difference, and in chronic epilepsy, either drug can be highly effective. Piracetam is an unusual drug which is uniquely effective in myoclonus and which has no effect in other types of epilepsy. It is most used in the treatment of myoclonus in the progressive myoclonic epilepsy syndromes. Some drugs exacerbate absence or myoclonic seizures in the generalized epilepsies, or indeed precipitate myoclonus for the first time in susceptible patients. Phenytoin has been reported to worsen the myoclonus in the Lafora body disease, and carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and phenytoin can aggravate myoclonus in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Other drugs which can be used as first-line therapy, but which have less reliable effects are levetiracetam, lamotrigine, topiramate, zonisamide, and the benzodiazepines. Ethosuximide is another highly effective drug but is largely ineffective in controlling generalized tonicclonic seizures, which often coexist with absence seizures. Where valproate is inappropriate or ineffective, other agents which can be used are levetiracetam, lamotrigine, topiramate, zonisamide, and the benzodiazepines. The myoclonus in the symptomatic generalized, Atypical absence, atonic, and tonic seizures these seizure types occur in the context of the LennoxGastaut syndrome or the other severe epileptic encephalopathies. The drug treatment is essentially similar for each, although full control of seizures is usually not possible. Levetiracetam has promise in these types of epilepsy on an anecdotal level but formal studies are limited. Topiramate and zonisamide have been shown to be effective in various open and controlled studies. Although large fortunes have been sunk into pharmacogenetics, no genetic predisposition has been identified in any situation which helps predict who will respond and who will not to any specific drug. Given the heterogeneity of epilepsy and the importance of environmental factors, this is perhaps not surprising. Prescribing patterns also vary depending on other factors such marketing pressures, the medical system, teaching, and information sources and there are surprisingly large differences in the relative use of drugs in different countries. Rufinamide is also useful in the various seizure types in the LennoxGastaut syndrome and is licensed only for this indication. Drugs which exacerbate seizures Carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine are frequently reported to exacerbate atypical absence and tonic seizures.

© 2025 Adrive Pharma, All Rights Reserved..