General Information about Citalopram

Like any medication, citalopram could work together with different medicine. It is essential to inform your physician of another drugs you are currently taking, together with over-the-counter drugs, dietary supplements, and natural cures. Some medication may interact with citalopram and increase the risk of serotonin syndrome, a potentially life-threatening situation that occurs when serotonin ranges turn into too high. It can be essential to avoid alcohol while taking citalopram, as it can increase the chance of unwanted effects.

Citalopram, commonly recognized by its model name Celexa, is a prescription medication used for the therapy of despair. It belongs to the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) class of medication, which work by increasing the levels of serotonin in the mind. This neurotransmitter is answerable for regulating mood, emotions, and behaviors. Citalopram is on the market in both pill and liquid form and is usually taken as quickly as a day.

Most individuals experience some side effects when taking citalopram, however these are often mild and short-term. The most common side effects include nausea, dry mouth, dizziness, and drowsiness. Less widespread side effects could embrace modifications in appetite, weight, or sexual function. Some individuals can also experience agitation, mood swings, or modifications in sleep patterns. It is important to discuss any side effects together with your doctor, as they could be able to modify your dosage or change you to a special treatment.

The primary use of citalopram is for the treatment of melancholy. It is FDA-approved for adults over the age of 18, and has been shown to be effective in managing signs of main depressive disorder. It is also used off-label for different mood issues such as bipolar dysfunction, nervousness problems, and obsessive-compulsive dysfunction. In some circumstances, citalopram can also be prescribed for premenstrual dysphoric dysfunction (PMDD), a extreme form of premenstrual syndrome.

It isn't really helpful to abruptly cease taking citalopram with out consulting your physician first. This can result in withdrawal signs corresponding to dizziness, flu-like signs, and electrical shock sensations. Your doctor will work with you to slowly lower the dosage over time to keep away from these signs. It can be essential to observe the prescribed dosage and not to exceed it, as this could result in an overdose.

In conclusion, citalopram is a commonly prescribed treatment for the treatment of despair. It is effective in restoring stability to the degrees of serotonin in the mind, which may help manage signs of depression. However, like several treatment, it is essential to talk about any concerns or side effects along with your physician. With correct use and monitoring, citalopram can be a useful software in managing despair and improving general well-being.

Citalopram works by inhibiting the reuptake of serotonin, allowing more of the neurotransmitter to remain in the synaptic hole between nerve cells. This leads to an increase in the availability of serotonin, which promotes a steady mood and emotional state. By restoring stability to serotonin levels, citalopram helps to minimize back emotions of sadness, hopelessness, and anxiety which may be commonly associated with depression.

In 1958 medications ok to take while breastfeeding discount citalopram 20 mg online, Rasmussen described three children in whom the clinical problem consisted of intractable focal epilepsy in association with a progressive hemiparesis. The cerebral cortex disclosed a mild meningeal infiltration of inflam matory cells and an encephalitic process marked by neu ronal destruction, gliosis, neuronophagia, some degree of tissue necrosis, and perivascular cuffing. Many additional cases were soon uncovered and Rasmussen was able to summarize the natural history of 48 personally observed patients (see the often cited monograph by Andermann). Recent studies suggest that a conversion-hysterical disorder accounts for most cases, even in males, and that malingering is rare but this has certainly not been our experience. Three broad categories of psychogenic states seem to generate pseudoseizures: (1) panic disorder that is itself common in people with epilepsy; (2) dissociative disorders, in which convulsions are typically prolonged, resembling generalized tonic-clonic seizures, or alter natively, swooning as in a faint or presyncopal spell, or blank spells that closely simulate absence seizure; and (3) malingering, the deliberate feigning of seizures to avoid certain situations. Usually, the unconventional motor display in the course of a nonepileptic seizure is sufficient to identify it as such: completely asynchronous thrashing of the limbs and repeated side-to-side movements of the head; strik ing out at a person who is trying to restrain the patient; hand-biting, kicking, trembling, and quivering; pelvic thrusting and opisthotonic arching postures; and scream ing or talking during the ictus. It is helpful to observe that the eyes are kept quietly or forcefully closed in pseudoseizure whereas the lids are open or show clonic movement in epilepsy. Psychogenic spells are likely if attacks are prolonged (many minutes, even hours), if there is rapid breathing (whereas apnea is typical dur ing and after a seizure), or if there is tearfulness after an episode. Pseudoseizures tend to occur in the presence of observers, to be precipitated by emotional factors. With few exceptions, tongue-biting, incontinence, hurtful falls, or postictal confusion are lacking but if the tongue is bit ten in a pseudoseizure it is usually the front, compared to the lateral tongue injury that is characteristic of an epileptic attack. Incontinence does not assist in making a clear distinction from epileptic seizures. Another clue to non-epileptic seizures in our experi ence has been highly resistant epilepsy in an individual with normal intellect and normal brain imaging. Often in these persons in particular, there has been a background of unexplained medical problems, previous psychologi cal problems (depression, panic disorder, overdose, self harm, addiction), and a life story that includes intense emotional trauma. Prolonged fugue states usually prove to be manifestations of hysteria or a psychopathy, even in a known epileptic. The serum creatine kinase levels are normal after nonepileptic seizures; this may be helpful in distin guishing them from epilepsy. This discharge arises from an assemblage of excitable neurons in any part of the cerebral cortex and possibly in secondarily involved subcortical structures as well. In the proper circumstances, a seizure discharge can be initiated in an entirely normal cerebral cortex, as when the cortex is activated by ingestion of drugs, or by withdrawal from alcohol or other sedative drugs. A special mechanism that ostensibly creates a secondary seizure focus, "kindling," is the result of repeated stimu lation with subconvulsive electrical pulses from an estab lished focus elsewhere; it is known to occur in animal models but is a controversial entity in humans. Each of these has been challenged but is sup ported by considerable data and together they serve as a reasonable model, as noted below. Some of the electrical properties of a corti cal epileptogenic focus suggest that its neurons have been deafferented. Neurons in these circumstances are hyperexcitable, and they may chronically remain in a state of partial depolarization, able to fire irregularly at rates as high as 700 to 1,000 per second. The cytoplasmic membranes of such cells have an increased ionic perme ability, which renders them susceptible to activation by hyperthermia, hypoxia, hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, and hyponatremia, as well as by repeated sensory. As an example, epileptic foci induced in the animal cortex by the application of penicillin are characterized by spontaneous interictal discharges, during which the neurons of the discharging focus exhibit large, calcium mediated paroxysmal depolarizations (depolarizing shifts), followed by prolonged afterhyperpolarizations. The latter are caused in part by calcium-dependent potassium currents, but enhanced synaptic inhibition also plays a role. The spread of seizures depends on factors that activate neurons in the focus or inhibit those surrounding it. Biochemical studies of neurons from a seizure focus have not greatly clarified the problem. Levels of extracel lular potassium are elevated in glial scars near epileptic foci, and a defect in voltage-sensitive calcium channels has also been postulated. Epileptic foci are known to be sensitive to acetylcholine and to be slower in binding and removing it than is normal cerebral cortex. Once the intensity of the seizure discharge exceeds a certain point, it overcomes the inhibitory influence of surround ing neurons and spreads to neighboring cortical regions via short corticocortical synaptic connections. This suggests that seizures could be triggered either by a change in central thalamic rhythm generators or a subtle alteration in the electrical activity in the region of a focal lesion. Of interest are the findings of Litt and colleagues that in a small number of patients there are prolonged bursts of seizure-like activity detected by sophisticated techniques even days before the onset of temporal lobe seizures. Their proposal is that these events cause a cascade of electrophysiologic changes that very gradually culminate in a seizure. If unchecked, cortical excitation spreads to the adjacent cortex and to the contralateral cortex via inter hemispheric pathways, and also to anatomically and functionally related pathways in subcortical nuclei (par ticularly the basal ganglionic, thalamic, and brainstem reticular nuclei). The spread of excitation to the subcortical, thalamic, and brainstem centers corresponds to the tonic phase of the seizure and to loss of conscious ness as well as to the signs of autonomic nervous system overactivity (salivation, mydriasis, tachycardia, increased blood pressure). Soon after the spread of excitation, a diencephalic inhibition begins and intermittently interrupts the sei zure discharge, changing it from the persistent tonic phase to the intermittent bursts of the clonic phase. The intermittent clonic bursts become decreasingly frequent and finally cease altogether, leaving in their wake an "exhaustion" (paralysis) of the neurons of the epileptogenic focus and a regional increase in permeability of the blood-brain barrier and regional edema in magnetic resonance images. Plum and associates observed a two- to threefold increase in glucose utilization dur ing seizure discharges and suggested that the paralysis that follows might be a result of neuronal depletion of glucose and an increase in lactic acid. However, inhibi tion of epileptogenic neurons may occur in the absence of neuronal exhaustion. The exact roles played by each of these factors in postictal paralysis of function are not settled. Insights to absence seizures have been obtained from animal models of bilaterally synchronous 3-per-second high-voltage spike-and-wave discharges.

A common com bination is the addition of gabapentin to an opioid such as morphine treatment jerawat di palembang buy citalopram on line amex, and perhaps not surprisingly, this was superior to either drug alone in a crossover trial in patients with postherpetic neuralgia and diabetic neuropathy con ducted by Gilron and colleagues but at the expense of side effects and lower tolerated doses of both drugs. Table preparations may provide considerable relief in posther petic neuralgia and some painful peripheral neuropa thies, but they are totally ineffective in others. Several types of spinal injections, including epidural, root, and facet blocks, have long been used for the treat ment of pain. Injections of epidural corticosteroids or mixtures of analgesics and steroids are helpful in selected cases of lumbar or thoracic nerve root pain, and occasion ally in painful peripheral neuropathy; but precise criteria for the use of this measure are not well established. Several studies do not support a beneficial effect but there is little doubt, in our view, that quite a few patients are helped, if only for several days or weeks (see Chap. Their m therpe c use in our experience has been for thoracic radiculitis from shingles, chest wall pain after thoracotomy, and diabetic radiculopathy. Injection of anal gesic compounds into and around facet joints and the extension of this procedure, radiofrequency ablation of 8-3 summarizes the main analgesics (nonnar cotic and narcotic), antiepileptics, and antidepressant drugs in the management of chronic pain. Despite these drawbacks, we have found both of these approaches very useful when pain can be traced to a derangement of these joints, as discussed in Chap. Only when a variety of analgesic medications (including opioids) and only when certain practical measures, such as regional analgesia or anesthesia, have completely failed, should one turn to neurosurgical pro cedures. Also, one should be very cautious in suggesting a procedure of last resort for pain that has no established cause as, for example, limb pain that has been incorrectly identified as causalgic because of a burning component but where there has been no nerve injury. The least-destructive procedure consists of surgical exploration for a neuroma if a prior injury or opera tion may have partially sectioned a peripheral nerve. Magnetic resonance imaging of the region should be performed first and will demonstrate most such lesions, but we are uncertain 300 mg three times daily; it should be used very cautiously in patients with heart block and has fallen very much out of favor in many centers, partly due to cardiac conduction abnormalities during and after the infusion. Reducing sympathetic activity within somatic nerves by direct injection of the sympathetic ganglia in affected regions of the body (stellate ganglion for arm pain and lumbar ganglia for leg pain) has met with mixed success in neuropathic pain, including that of causalgia and reflex sympathetic dystrophy. A variant of this technique uses regional intravenous infusion of a sympathetic-blocking drug (bretylium, guanethidine, reserpine) into a limb that is isolated from the systemic circulation by the use of a tourniquet. This is known as a "Bier block," after the devel oper of regional anesthesia for single-limb surgery. These techniques, as well as if all small neuromas are visual ized, and it is this ambiguity that justifies exploration. This procedure, in which there is now spinal electrical stimulator, usually adjacent to the pos a resurgence of interest, has afforded only incomplete relief in our patients and may be difficult to maintain in place. However Kemler and colleagues found a sustained reduction in pain intensity and an improved quality of life in patients with intractable reflex sympathetic dys trophy, even after 2 years in a randomized trial. It is clear that careful selection of patients is the best assurance of a good outcome. We can add from experience with our patients that a temporary trial of the stimulator is advisable before committing to its permanent use. The ill-advised use of nerve section and dorsal rhizotomy as definitive measures for the relief of regional pain was discussed above under "Treatment of Intractable Pain. These forms of treatment have been under study for many decades and have given variable results but the most consistent responses to regional sym pathetic blockade are obtained in cases of true causalgia resulting from partial injury of a single nerve. A number of other treatments have proven successful in some patients with reflex sympathetic dystrophy and other neuropathic pains but the clinician should be cau tious about their chances of success over the long run. A novel one of these has been the use of bisphosphonates (pamidronate, alendronate), which have been beneficial in painful disorders of bone, such as Paget disease and metastatic bone lesions. It is theorized that this class of drug reverses the bone loss consequent to reflex sympa thetic dystrophy but how this relates to pain control is unclear (Schott, 1997). Electrical stimulation of the poste rior columns of the spinal cord by an implanted device, as discussed below, has become popular. Another treat ment of last resort is the intravenous or epidural infusion of drugs such as ketamine; sometimes this has a lasting effect on causalgic pain. The approaches enumerated here are usually under taken in sequence; a combination of drugs-such as and lower trunk. This may be done as an open operation or as a transcutaneous procedure in which a radiofre and thermoanesthesia may last a year or longer, after thoracic level, effectively relieves pain in the opposite leg quency lesion is produced by an electrode. The analgesia which the level of analgesia tends to descend and the pain tends to return. Bilateral tractotomy is also feasible but with greater risk of loss of sphincteric control and, at higher levels, of respiratory paralysis. Motor power is nearly always spared because of the position of the corti cospinal tract in the posterior part of the lateral funiculus. High cervical transcutaneous cor dotomy has been used successfully, with achievement of analgesia up to the chin. Commissural myelotomy by longitudinal incision of the anterior or posterior com missure of the spinal cord over many segments has also been performed, with variable success. Lateral medullary tractotomy is another possibility but must be carried almost to the mid-line to relieve cervical pain. The risks of this latter procedure and also of lateral mesencephalic tractotomy (which may actually produce pain) are so great that neu rosurgeons have abandoned these operations. Stereotactic surgery on the thalamus for one-sided chronic pain is still used in a few centers and the results have been instructive. Lesions placed in the ventroposterior nucleus are said to diminish pain and thermal sensation over the contralateral side of the body while leaving the patient with all the misery or affective experience of pain; lesions in the intralaminar or parafascicular-centromedian nuclei relieve the painful state without altering sensation able benefits to the patient, they are now seldom used. Because these procedures have not yielded predict been mirror therapy in which the patient is instructed to perform movements in the painful arm while watch ing the same moves in a mirror, made by the unaffected arm. The majority of patients in one blinded trial ben efitted in terms of pain and mobility, but this study by Cacchio and coworkers included only patients with strokes and paretic limbs, not those with peripheral nerve injury. Attempts to quantify the benefits of these techniques-judged usually by a reduction of drug dosage-have given mixed or negative results. Nevertheless, it is unwise for physicians to dismiss these methods, as well-motivated and apparently psychologi cally stable persons have reported subjective improve ment with one or another of these methods and in the final analysis, this is what really matters.

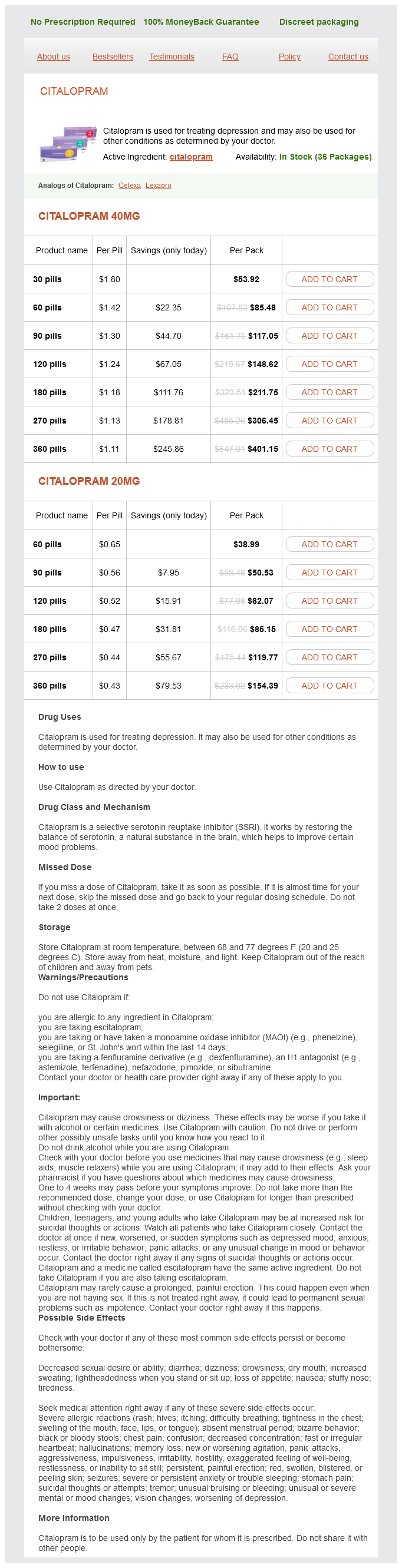

Citalopram Dosage and Price

Citalopram 40mg

- 30 pills - $53.92

- 60 pills - $85.48

- 90 pills - $117.05

- 120 pills - $148.62

- 180 pills - $211.75

- 270 pills - $306.45

- 360 pills - $401.15

Citalopram 20mg

- 60 pills - $38.99

- 90 pills - $50.53

- 120 pills - $62.07

- 180 pills - $85.15

- 270 pills - $119.77

- 360 pills - $154.39

The first (fast) pain is transmit ted by the larger (A-8) fibers and the second (slow) pain treatment vs cure generic citalopram 40 mg buy, which is somewhat more diffuse and longer lasting, by the thinner, unmyelinated C fibers. Deep pain from visceral and skeletomuscular struc tures is usually aching in quality; if intense, it may be sharp and penetrating (knife-like). Occasionally visceral derangements cause a burning type of pain, as in the "heartburn" of esophageal irritation and rarely in angina pectoris. It is diffuse and poorly localized, and the margins of the painful zone are not well delineated, presumably because of the relative paucity of nerve endings in vis cera. First, there is tenderness at remote superficial sites ("referred hyperalgesia") and, second, an enhanced pain sensitivity in the same and in nearby organs ("visceral hyperalgesia"). The concept of visceral hyperalgesia has received considerable attention in a number of pain syndromes in reference to the transition from acute to chronic pain, particularly in headache. Deep pain has indefinite boundar ies and its location is distant from the visceral structure involved. It tends to be referred not to the skin overlying the viscera of origin but to other areas innervated by the same spinal segment (or segments). This pain, projected to some fixed site at a distance from the source, is called referred pain. The ostensible explanation for the site of referral is that small-caliber pain afferents from deep structures project to a wide range of lamina V neurons in the dorsal horn, as do cutaneous afferents. Because the nociceptive receptors and nerves of any given visceral or skeletal structure may project upon the dorsal horns of several adjacent spinal or brainstem seg ments, the pain from these structures may be fairly widely distributed. For example, afferent pain fibers from cardiac structures, distributed through segments T1 to T4, may be projected to the inner side of the arm and the ulnar border of the hand and in relation to peripheral nerve injuries (see "Peripheral Nerve Pain" and Chap. Peripheral nerve lesions have been shown to induce enduring derangements of central (spinal cord) processing (Fruhstorfer and Lindblom). For example, avulsion of nerves or nerve roots may cause chronic pain even in analgesic zones (anesthesia dolorosa or "deaffer entation pain"). In experimentally deafferented animals, neurons of lamina sal horns of the spinal cord is activated, additional noxious stimuli may heighten the activity in the whole sensory field ipsilaterally and, to a lesser extent, contralaterally. The regions of projection of pain that originate in the bones and adjacent ligamentous structures have been called by Kellgren, "sclerotomes. Although dermatomes and sclerotomes overlap, the patterns are slightly different as shown in. These scleroto matous projections are useful to neurologists in analyzing the origins of unusual pains of the cranium, spine, and limbs (see Chaps. Once this pool of sensory neurons in the dor arm (Tl and T2) as well as the precordium V begin to discharge irregularly in the absence of stimulation. Later the abnormal discharge subsides in the spinal cord but can still be recorded in the thalamus. Consequently, painful states such as causalgia, spinal cord pain, and phantom pain are not abolished simply by cutting spinal nerves or spinal tracts. Certainly none of these phenomena can adequately explain the entire story of chronic pain. It is likely that structural changes in the spinal cord, of the type alluded to above, are able to produce persistent stimulation of pain pathways. Indo and colleagues review the molecular changes in the spinal cord that may give rise to persis tence of pain after the cessation of an injurious episode. It is an open question whether the early treatment of pain may prevent the cascade of biochemical events that allows for both spread and persistence of pain in condi tions such as causalgia, but it has been the experience of most clinical pain experts that preemptive treatment of certain painful conditions. Furthermore, prolonged stimulation of pain receptors sensitizes them, so that they become responsive to even low grades of stimulation, even to touch (allodynia). Once it becomes chronic, any pain may spread quite widely in a vertical direction on one side of the body. On the other hand, painful stimuli aris ing from a distant site exert an inhibitory effect on segmental nociceptive flexion reflexes in the leg, as demonstrated by DeBroucker and colleagues. Yet another clinical peculiarity of segmental pain is the reduction in power of muscle contrac tion that it may cause (reflex paralysis, or algesic weakness). Several theories have been offered, none of which satis factorily accounts for all the clinically observed phenom ena. One hypothesis proposes that in an injured nerve, the unmyelinated sprouts of A-8 and C fibers become capable of spontaneous ectopic excitation and after discharge and are susceptible to ephaptic activation. A second proposal derives from the observation that these injured nerves are also sensitive to locally applied or intravenously administered catecholamines because of an overabundance of adrenergic receptors on the regenerating fibers. Either this mechanism or ephapse (nerve-to-nerve cross-activation) is thought to be the basis of causalgia (persistent burning and aching pain in the territory of a partially injured nerve and beyond) and its associated reflex sympathetic dystrophy; either would explain the relief afforded in these conditions by sym pathetic block. Since pain embodies this element, psycho logic conditions assume great importance in all persistent painful states. It is of interest that despite this strong affective aspect of pain, it is difficult to recall precisely, or to reexperience from memory, a previously experi enced acute pain. Some individu als-by virtue of training, habit, and phlegmatic tem perament-remain stoic in the face of pain, and others react in an opposite fashion. In this regard, it is important to emphasize that pain may be the presenting or predominant symptom in a depressive illness (Chap. The projections of pain from osteal and periosteal structures such as ligaments were established by the injection of hypertonic saline or formic acid into the upper extremity (A) and lower extremity (B) and can also be found in the articles of Kellgren. It is noteworthy, how ever, that on functional imaging studies regions of the cerebrum that are activated by experimentally induced physical pain overlap with those for the experience of emotional pain, as reported by Wager and colleagues. Finally, a comment should be made about the dev astating behavioral effects of chronic pain. Patients in pain may seem irra tional about their illness and make unreasonable demands on family and physician. Characteristic is an unwillingness to engage in or continue any activity that might enhance their pain.

© 2025 Adrive Pharma, All Rights Reserved..