General Information about Bactroban

Bactroban should not be used on open wounds or broken skin, as this may improve the danger of absorption and potential antagonistic effects. It can also be not beneficial to be used on mucous membranes, corresponding to the within of the nose or mouth. If the infection does not improve inside three to five days of utilizing Bactroban, the physician must be notified because the bacteria may be resistant to the treatment.

In conclusion, Bactroban is an effective remedy for various pores and skin infections attributable to bacteria. It is necessary to observe the prescribed dosage and instructions, and to report any side effects to the physician. With correct use, Bactroban can help clear up pores and skin infections and prevent them from spreading or recurring.

This treatment is commonly used for treating impetigo, a extremely contagious skin infection commonly seen in young kids. Impetigo is characterized by red sores on the face, particularly across the mouth and nose, and can even occur on other parts of the physique. Bactroban works by killing the micro organism that cause impetigo, allowing the skin to heal and stopping additional spread of the an infection.

Bactroban, also called mupirocin, is a prescription medication primarily used for treating pores and skin infections brought on by bacteria. It belongs to a class of antibiotics called topical antibiotics, that are applied on to the pores and skin. Bactroban is available within the form of a cream, ointment, or nasal ointment.

Aside from impetigo, Bactroban may additionally be used to deal with different types of skin infections corresponding to folliculitis, an an infection of the hair follicles, and folliculitis barbae, an infection of the hair follicles on the face and neck. It is also efficient against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), a sort of bacteria that's resistant to many widespread antibiotics.

Bactroban is mostly well-tolerated, however like several medicine, it could cause side effects in some people. Common unwanted side effects embody burning, stinging, or itching on the website of utility. These unwanted aspect effects are often gentle and go away on their very own. In rare instances, individuals could experience severe allergic reactions, together with rash, itching, swelling, and issue respiration. If these symptoms occur, medical consideration should be sought instantly.

As with any antibiotic, it is necessary to full the complete course of therapy, even when symptoms enhance. Stopping the treatment too soon might lead to a recurrence of the infection and may improve the risk of antibiotic resistance.

When utilizing Bactroban, you will need to comply with the instructions supplied by the doctor or pharmacist. It ought to be utilized solely to the affected space of the pores and skin and shouldn't be ingested. It is often really helpful to use a skinny layer of the cream or ointment to the affected space thrice a day for ten days, or as prescribed by the doctor.

Colchicine toxicity acne grades order 5 gm bactroban fast delivery, mainly in patients with renal failure, has been linked to increased numbers of metaphase mitoses, epithelial pseudo-stratification and loss of polarity, and an increase in the proliferation zone as demon- strated by Ki67 staining. In patients with therapeutic levels of colchicine, a villous atrophy/hyperplastic crypt pattern has been described in the jejunum. Mitotic arrest with numerous metaphase mitoses in crypt epithelium is also a characteristic feature of recent taxane chemotherapy. Villous atrophy in the ileum or small intestine with lymphocytic ileo-colitis has been reported with ticlodipine and Cyclo 3 Fort (a veinotonic) [407,408]. Finally, successful chemotherapeutic ablation of primary tumours of the small intestine, notably malignant lymphoma, can induce perforation of the intestine through the necrotic tumour and strictures can develop later [409]. Miscellaneous inflammatory conditions of the small intestine Numerous miscellaneous inflammatory conditions affect the small bowel. Two more general pathological phenomena not uncommonly presenting to the surgical pathologist and providing a taxing differential diagnosis, often requiring clinical, therapeutic and radiological correlation, are ulceration and/or perforation and tissue eosinophilia of the small intestine. Ulceration in the small bowel Small bowel ulcers distal to the duodenum were first described by Baillie in 1795. Between 1956 and 1979, 59 cases were seen at the Mayo Clinic, which represented approximately 4 cases per 100 000 new patients registered. A steady increase in the number of patients was found in each decade of life from the second to the seventh [410]. Microscopically the ulcer crater is filled with a layer of necrotic and granulation tissue with a variable inflammatory reaction, usually ending at the ulcer edge. Vascular pathological changes such as congestion and narrowing or occlusion of submucosal vessels may or may not be present. The differential diagnosis of these penetrating small intestinal ulcers, which may be multiple, is broad and includes congenital malformation, inflammation, ingestion of a foreign body, entrapment of a pill, or any other trauma, vascular abnormalities, adhesions, chemical irritation and neoplasia, especially lymphoma and (neuro-)endocrine tumours in the ileum. Ischaemic duodenal ulcer has been reported as an unusual presentation of sickle cell anaemia [412]. Some of these features may be less pronounced in the more chronic, fibrotic and burnt-out phases of the disease [109,298]. In young children, obscure ulceration may represent a distinct inherited disease, intractable ulcerating enterocolitis of infancy [413]. The pathological features of ulceration related to bacterial infection may be non-specific and microbiological investigation may be required. Nevertheless, the characteristic pathological features of ischaemia should be demonstrable in the adjacent small intestinal mucosa. Jejunal and ileal ulceration may be peptic in origin, especially in ZollingerEllison syndrome [414]. Peptic digestion of the ulcer bed and multiplicity of ulcers should prompt investigation of acid secretion and serum gastrin levels. Vascular pathology, including vasculitis and irradiation enteritis, may all cause perforating ulceration in the small bowel. Ulcerative jejunitis, effectively representing an early stage of lymphoma in the small bowel, has been considered elsewhere. Suffice it to say that the features of lymphoma may be very subtle in ulcers of the jejunum and ileum, and evidence of lymphoid malignancy should be diligently sought by morphological, histochemical and, if necessary, molecular biological methodology. Once all these avenues of investigation have been exhausted, drugs should be strongly considered as the cause of small intestinal ulceration. Despite comprehensive searching for evidence of drug ingestion, there will remain some cases of small intestinal ulceration that have to be regarded as primary idiopathic disease [417]. Despite regular ileoscopy during colonoscopy and the advent of endoscopic methods, this small patient group remains enigmatic at present. Eosinophilic infiltrates in the small intestine Eosinophils are constitutively present in the gastrointestinal mucosa outside the oesophagus. Eosinophilic disorders can be separated in to primary (idiopathic) and secondary diseases, primary having no known cause and secondary being due to other illnesses resulting in tissue eosinophilia. Primary eosinophilic enteritis has been called allergic gastroenteropathy because a subset of patients has an associated allergic component. Although considered idiopathic, an allergic mechanism may be involved because most patients exhibit increased food-specific IgE levels. Tissue eosinophilia of the small intestine is also seen in malignant lymphoma and in the inflammatory fibroid polyp. In the absence of evidence of secondary disease, a diagnosis of eosinophilic (gastro)enteritis can be considered. In the Mayo Clinic 40 patients were identified from 1950 to 1987 from medical records documenting more than 4 million individuals. It has been suggested that the clinical features may reflect the extent, location and depth of infiltration of the eosinophils. The Klein classification separates eosinophilic gastroenteritis in to mucosal and/or submucosal, muscular or (sub)serosal disease. Patients with mucosal disease present with vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, gastrointestinal bleeding, iron deficiency anaemia, malabsorption, protein-losing enteropathy or failure to thrive. If muscular layers are involved, obstruction or even acute abdomen has been recorded, whereas serosal involvement may be associated with evidence of ascites. The normal number of eosinophils has not been defined and may vary between pathology departments, depending on the techniques used but may also show geographical differences. The striking submucosal eosinophilic infiltrate, often with a distinct paucity of other inflammatory cell types, is accompanied by oedema.

Yersiniosis the appendix is not infrequently involved in ileal and mesenteric lymph nodal yersiniosis but disease may be confined to the appendix [57] acne inversa bactroban 5 gm order online. Inflammatory disorders of the appendix 487 individuals clinically suspected of appendicitis, compared with incidentally removed organs [74]. Viral appendicitis Viral appendicitis may account for the appendicectomy with lymphoid hyperplasia and no acute inflammation. However, viral infection may lead to erosion, secondary bacterial infection and acute appendicitis [28]. Implicated viruses include adenovirus, Coxsackievirus, measles virus and cytomegalovirus [75], the last being described in immunocompetent, as well as immunocompromised, patients with acute appendicitis [76]. There is no specific causative factor and it is probable that the condition results from incomplete resolution of an abscess in a retrocaecal appendix. Miscellaneous forms of appendicitis Polyarteritis nodosa can occasionally present as acute appendicitis without specific histological lesions in the appendix [80]. However, a similar focal necrotising arteritis of the appendix also occurs as an incidental finding, usually in young women, unrelated to appendicitis or any systemic disease [81]. Other causes of appendicitis include amoebiasis [85,86], balantidial infection [87], strongyloidiasis [88], mucormycosis [89], aspergillosis [90] and histoplasmosis [91]. The prevalence of appendiceal faecoliths in patients with and without appendicitis. Clinical manifestations of appendiceal pinworms in children: an institutional experience and a review of the literature. Intravascular lymphocytosis in acute appendicitis: potential mimicry of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. The role of Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis in granulomatous appendicitis. Ulcerative colitis of the ileum, and regional enteritis of the colon: a comparative histopathologic study. Ulcerative colitis with skip lesions at the mouth of the appendix: a clinical study. Sequelae of appendectomy, with special reference to intra-abdominal adhesions, chronic abdominal pain, and infertility. Perforated appendicitis within an inguinal hernia: case report and review of the literature. Acute appendicitis in adult neutropenic patients with haematological malignancies. Suppurative pylethrombophlebitis and multiple liver abscesses following acute appendicitis. Ileocolic intussusception in an adult caused by a granuloma of the appendiceal stump. Histopathology of interval (delayed) appendectomy specimens: strong association with granulomatous and xanthogranulomatous appendicitis. Balantidiasis: report of a fatal case with appendicular and pulmonary involvement. Eosinophilic appendicitis demonstration of Strongyloides stercoralis as a causative agent. Fatal mucormycosis presenting as an appendiceal mass with metastatic spread to the liver during chemotherapy-induced granulocytopenia. This chapter reviews appendiceal mucinous tumours, adenocarcinomas, endocrine tumours, goblet cell carcinoids, lymphomas and mesenchymal tumours, and ends with a brief discussion of metastatic tumours to the appendix. Abdominal pain that mimics acute appendicitis or an abdominal mass (sometimes ovarian) is the most common presentation [3,6,7,9], but a significant number are discovered incidentally. The mucinous epithelial cells are columnar and mucin rich and have elongated, mildly hyperchromatic nuclei, nuclear pseudo-stratification, rare mitoses and apoptotic nuclear debris [3,9,10]. Cystic tumours are lined by mucinous epithelium that can be partly villous, flat or attenuated. The prognosis of low grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms is dependent on the presence or absence of epithelial cells outside the appendix. Tumours that are confined to the appendix and have not ruptured have an excellent prognosis. Tumours that have ruptured may be associated with mucin spillage in to the peritoneal cavity. The presence of epithelial cells in the extra-appendiceal mucin, even if limited and confined to the right lower quadrant, increases the risk of recurrence [12,13]. Colonoscopy is usually advised in patients found to have appendiceal mucinous tumours, because of a significant association with synchronous and metachronous colorectal neoplasia. Adenocarcinoma Adenocarcinoma of the appendix is rare; Collins found an incidence of 0. Patients are usually in their fifth to seventh decades [1518] and have symptoms of appendicitis, although they may present with a palpable mass, obstruction, gastrointestinal bleeding or symptoms referable to metastases [7,1620]. In general, appendiceal adenocarcinomas manifest as either cystic mucinous tumours that are prone to rupture and spread to the ovaries and peritoneum or intestinal-type carcinomas that infiltrate the appendiceal wall and metastasise to lymph nodes and the liver. Mucinous adenocarcinoma accounts for approximately 40% of appendiceal adenocarcinomas [18]. Appendiceal nonmucinous carcinomas show a range of morphology of the invasive component. In some cases, the tumour has an appearance identical to colonic adenocarcinoma with malignant glands lined by columnar epithelium. In other cases, the malignant glands are tubular in shape, lined by cuboidal epithelium and associated with modest amounts of extracellular mucin. Signet-ring cell carcinoma is rare in the appendix and has a poor prognosis due to rapid dissemination within the peritoneal cavity [21]. The reported 5-year survival rate for patients with appendiceal adenocarcinoma ranges from 18.

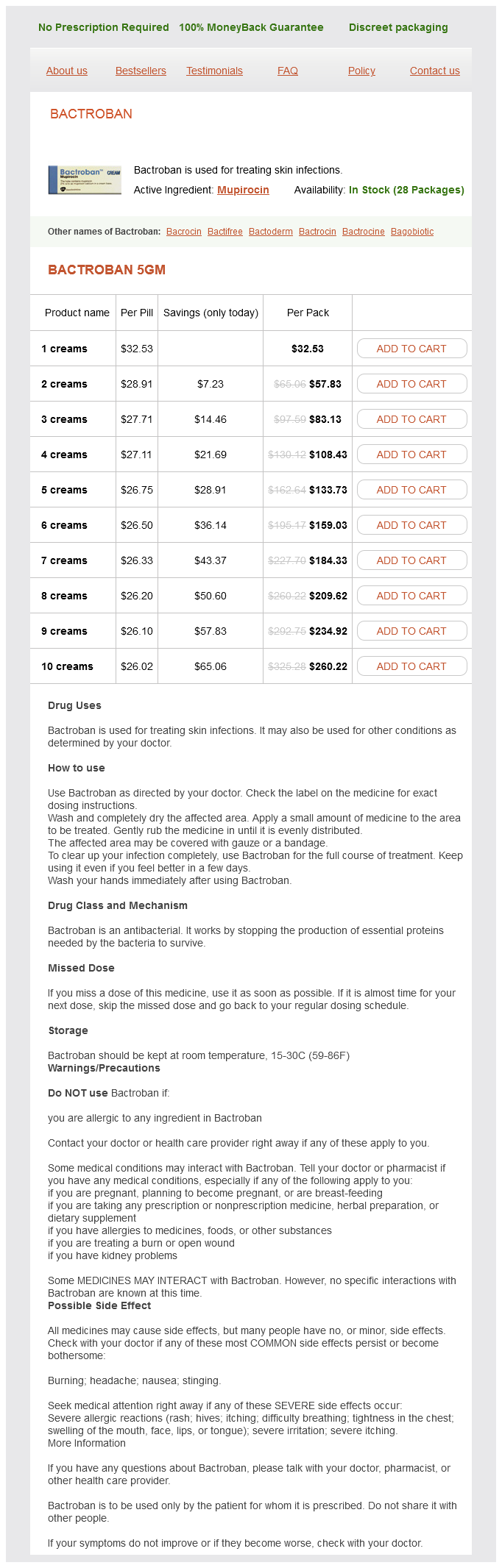

Bactroban Dosage and Price

Bactroban 5gm

- 1 creams - $32.53

- 2 creams - $57.83

- 3 creams - $83.13

- 4 creams - $108.43

- 5 creams - $133.73

- 6 creams - $159.03

- 7 creams - $184.33

- 8 creams - $209.62

- 9 creams - $234.92

- 10 creams - $260.22

Molecular mimicry between Helicobacter pylori antigens and H+ acne 6 dpo generic bactroban 5 gm visa, K+adenosine triphosphatase in human gastric auto-immunity. Association of Helicobacter pylori and gastric auto-immunity: a population-based study. Significant increase in antigastric autoantibodies in a long-term follow-up study of H. Immune response to Helicobacter pylori and its association with the dynamics of chronic gastritis in the antrum and corpus. Release of antigastric autoantibodies in Helicobacter pylori gastritis after cure of infection. High prevalence of manifestations of gastric auto-immunity in parietal cell antibody-positive type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetic patients. Early manifestations of gastric auto-immunity in patients with juvenile auto-immune thyroid diseases. Association of auto-immune type atrophic corpus gastritis with Helicobacter pylori infection. Evaluation of gastric cancer risk using topography of histological gastritis: a largescaled cross-sectional study. Significance of endoscopically visible blood vessels as an index of atrophic gastritis. Neuroendocrine differentiation in gastric adenocarcinomas associated with severe hypergastrinemia and/or pernicious anaemia. Epidemiologic, clinicopathologic, and economic aspects of gastroscopic screening of patients with pernicious anaemia. Gastric lesion in some megaloblastic anaemias: with special reference to the mucosal lesion in pernicious tapeworm anaemia. Atrophic auto-immune pangastritis: A distinctive form of antral and fundic gastritis associated with systemic autoimmune disease. Auto-immune enteropathy with severe atrophic gastritis and colitis in an adult: pro- 157 339. Emphysematous gastritis associated with invasive gastric mucormycosis: a case report. Phlegmonous gastritis associated with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome/pre-acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Changes in the mucosa of the stomach and duodenum during immunosuppressive therapy after renal transplantation. Treponema pallidum and Helicobacter pylori recovered in a case of chronic active gastritis. Significantly lower prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in uremic patients than in patients with normal renal function. Systemic mastocytosis involving the gastrointestinal tract: clinicopathologic and molecular study of five cases. Collagenous and lymphocytic colitis: systematic review and update of the literature. Lymphocytic gastritis in patients with coeliac sprue or spruelike intestinal disease. Lymphocytic gastritis prospective study of its relationship with varioliform gastritis. The pattern of involvement of the gastric mucosa in lymphocytic gastritis is predictive of the presence of duodenal pathology. Spontaneous remission of hypertrophic lymphocytic gastritis associated with hypoproteinemia. Clinical and endoscopic improvement of lymphocytic gastritis with eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Massive bleeding from multiple gastric ulcerations in a patient with lymphocytic gastritis and coeliac sprue. Effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the natural history of lymphocytic gastritis. Eosinophilic esophagitis attributed to gastroesophageal reflux: improvement with an amino acid-based formula. Disseminated infection of Pneumocystis carinii in a patient with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Gastric cryptosporidiosis: correlation between intensity of infection and histological alterations. Cytomegalovirus inclusions in the gastroduodenal mucosa of patients after renal transplantation. Cytomegalovirus infection of gastrointestinal endothelium demonstrated by simultaneous nucleic acid hybridization and immunohistochemistry. Endoscopic diagnosis of cytomegalovirus gastritis after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cytomegalovirus gastritis simulating cancer of the linitis plastica type on endoscopic ultrasonography. Gastric cytomegalovirus infection in bone marrow transplant patients: an indication of generalized disease. Herpes virus infection of the esophagus and other visceral organs in adults: incidence and clinical significance. Recovery of herpes simplex type 1 from the coeliac ganglion after renal transplantation. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: Report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Role of esophagogastroduodenoscopy in the initial assessment of children with inflammatory bowel disease. Upper gastrointestinal mucosal disease in pediatric Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis: a blinded, controlled study.

© 2025 Adrive Pharma, All Rights Reserved..